Domination of women has for centuries been the norm all over the world. Women have for long been considered and treated as second fiddle to men in aspects of social, political, economic, human rights and development. Women were never and have never been comfortable with this kind of arrangement but given a highly patriarchal society we live in, where every instrument of society is designed to perpetrate women domination, they had/have no choice but to accept and live with it.

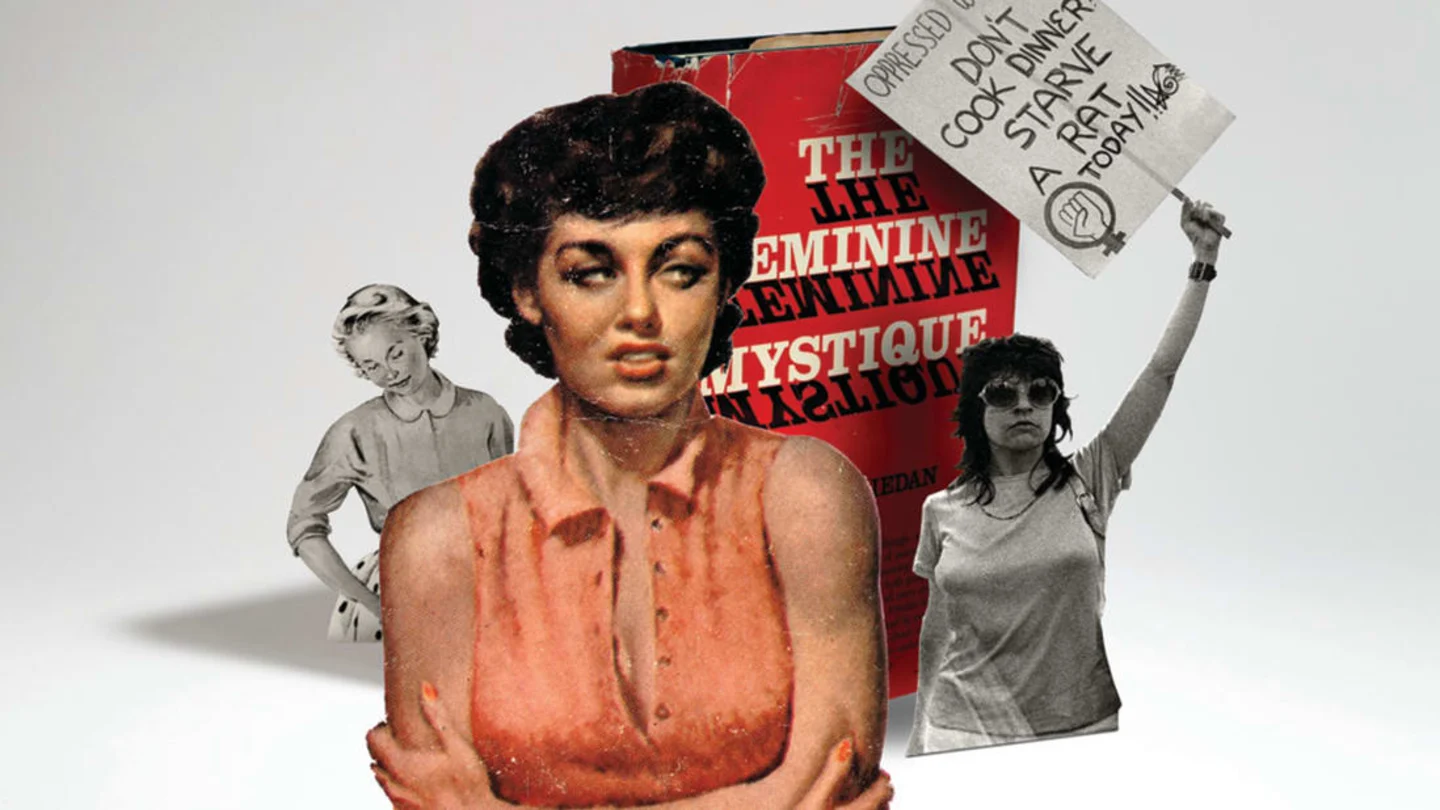

In her 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan is credited laying the foundation, and bringing into the public domain, a discussion that ultimately spearheaded women emancipation through subsequent women liberation movements in America. The book itself and the legacy it espouses might be contested, but Friedan’s work in exposing what she referred to as the ‘problem that has no name’, was read widely and it’s wide readership played a very important role by voicing the struggles of women in their millions, who had for long been held captive by the 1950s conservative myth that was the so-called bliss of the modern suburban housewife in America. Many women had for long silently felt alone and crazy in their feelings of emptiness, and Friedan, by exposing the problem that has no name, brought a lot of relief to many women by telling them that they were not alone in feeling empty and dissatisfied, and that its not their fault but society’s.

For the first time ever, women had a voice that spoke for them, that told them that it was okay to feel the way they felt and that they did not need to hide it, or deny it or even try to fight it. Through the feminine mystique, Friedan made impossible and even impractical to pretend that the problem did not exist. In her words; “It is no longer possible to ignore that voice, to dismiss the desperation of so many American women. This is not what being a woman means, no matter what the experts say. For human suffering there is a reason; perhaps the reason has not been found because the right questions have not been asked, or pressed far enough…. The women who suffer this problem have a hunger that food cannot fill…. We can no longer ignore that voice within women that says: “I want something more than my husband and my children and my home.” Friedan, for the first time, empowered women with a platform to voice their suffering without being labelled as mad or their concerns called baseless.

Far from being radical, as conservatives tried to label it, the feminine mystique did argue that by creating space for them outside the home, not instead of their domestic duties but in addition to it, women would be helped to become better mothers and wives. Friedan however, blames women for being responsible for their own predicament, for not being able to clearly articulate their concerns and instead suffer in silence. Yet despite these limitations, the feminine mystique was a source of inspiration for many women who had been sociologically been domesticated by the mythology of the 1950s American housewife. Whereas some would argue that it was born out of ignorance about social evolution of women, Friedan argued that it was rather, a conscious and deliberate attempt to push women out of the positions that they rightfully and ably occupied in the absence of men, and to also suppress the memories of gains and victories that women had realized during their decade or so, of self-exploration and self-expression outside the home.

Most problems in marriage were blamed on the woman being ‘too aggressive’ or being ‘too efficient’, or being ‘masculine’ and ‘sexually frigid’. Friedan said that in many of such cases, psychiatrists would suggest that when husband meted violence upon their wives, it was justified as an attempt to correct the unhealthy role reversal in the family, allowing opportunity for the women to be punished for their domineering character and allow the husbands to regain and reclaim their masculine identity. In other words, when husbands violently abused their wives through beatings, marital rape etc., they were only trying to reassert their position as men. Friedan, at the same time describes it as a conformity and passivity period, where there were already meaningful gains for women, such as acceleration in women education, and more and more women were acquiring gainful employment.

The glaring reality of a changing world set aside, Friedan points out that the growing media of television and women’s magazines did not relent it its desire to continue perpetrating the myth of feminine mystique. So much so that even when more and more women were fast developing thoughts of negativity towards marriage, they were nevertheless continuously made to feel that they are supposed to be happy despite the vivid reality, and that if they were unhappy, they had themselves to blame for their unhappiness.

In The Feminist Mystique, Betty Friedan does not bring out anything new when she comments about the disadvantage under which women were expected to live. What was new however, was her portrayal of the mid-1950s America, where the patriarchal society, was fully convinced and wholly believed that the state of affairs in the male-female dynamic was intended for the good of the women. The institutional men of the time actually believed that by keeping women in domesticated positions, they were actually helping women, that it relived women of the burdens of life, work and struggle, that by keeping them in the home, women were being afforded the chance to live the ‘easy life’.

Friedan probes into the lives of the middleclass American women in the aftermath of the Second World War, and attempts to provide a glimpse into the immense potential of women that was being sacrificed in the name of maintaining family stability. Following the women’s movement of the 1920s, women had gotten rid of the ancient values of the old Victorian era, achieved voting rights and built careers and independent lives. As men in their millions were conscripted and taken off to fight in the Second World War, women took control and filled the gap left by departing men in many previously male-dominated spheres, and doing it well in keeping the important sectors running, such as working in factories, as technicians producing war materials and repairing damaged ones, nursing wounded soldiers, as well as clerical and administrative duties.

However, when men returned from the war, there was an attempt to reclaim their place in social and administrative management, and women had to ‘relinquish their caretaker positions’. As Friedan puts it, there was an attempt and successfully so, to create/invent a legitimate occupation or position for women, which was termed as ‘homemaking’. The women being pushed into domestication had partaken in more productive, more satisfying and more socially impacting work. They knew they were capable of doing more than ‘homemaking’, and by being pushed back into the home to bear and rare children and to take care of the home, they found themselves having an unexplained longing, an emptiness that was hard, even impossible to describe. This emptiness is what Friedan called ‘the problem that has no name’.

The justification for women domination was so engraved in the social fabric that it was the expected norm and any practice to the contrary was seen as the exception, an anomaly, a fruitless pursuit of ungrateful, uncultured women whose ambitions would no-doubt lead to self-harm. So by continuing to set social restrictions on women, the 1950s American men believed that they were fulfilling their patriarchal responsibilities.

Friedan blamed the media for defining and perpetrating what she called ‘an idealized image of femininity’, a socialization construct which defined women and their roles in society. By this construct, women were expected to get a husband and keep him, produce and raise children, and always prioritize the needs of the husband and the children. This media construct perpetrated the myth that the modern American women saw any roles outside the home as ‘unfeminine’ and were not at all bothered by such as they were fully contented in the home, and that women wanted their husbands to make all major decisions concerning their lives. In the words of Friedan, the media promoted the notion that women ‘gloried in their role as women and were proud to describe themselves as ‘housewife’ by occupation’.

Femininity was being defined to fit the century-old patriarchal narrative that women are meant to play a supportive, subjective role to men, which oppressed and excluded the American housewife from all spheres of social life outside the home. Yet according to Friedan, femininity is set of un-deciphered traits that drive women. Friedan asserted that the patriarchal American society deliberately designed this perceived feminine mystique as a justification for pushing women out of the positions they had rightfully earned and faithfully executed for over a decade in the absence of the men. This was done, not for the benefit of the women as it was claimed by the media, but rather to reassert the positions of men as the leaders in the conservative social sphere.

Friedan exposes the tireless and deliberate effort by conservative patriarchy, to create an ideal social description of the ‘modern’ middleclass housewife. The media created and perpetrated the image of an ideal wife as one who is not bothered about acquiring an education, whose only preoccupation was to become a wife and mother, contented with maintaining the home and the comforts it provided for the husband. An ideal image of a happy woman was one comprised of early marriage, many children and giving up on education. The media also framed the narrative that although they were confined to the home, these women still had equal rights with their husbands, because women had the freedom to select the type of furniture, appliances and cars to have in their homes.

Women were expected to derive total happiness from beautifying themselves (dyeing their hair blonde) and caring for their homes, and feminine mystique was shaped as the cultural core of contemporary America over a decade after the Second World War ended. According to Friedan, women’s core dream was achieving perfection in their wifely and motherly duties, and their entire efforts directed towards acquiring these material goals (marriage and motherhood) and maintaining them well. Accordingly, women in the 1960s were socialized to pay little or no attention at all to matters outside their homes and be contented enough to proudly profess themselves as ‘career homemakers’. Women who found discomfort in conforming to this socialization were described as having neurotic abnormalities.

Since the post-second world war contemporary America decided to send women back into the home with the framing of ‘feminine mystique’, the image of the ideal wife became so entrenched that women felt they had to adhere to the submissive culture. ‘Sociology experts’ and the media made it seem like domestication was the best gift for modern suburban women and that all women were happy with the feminine mystique. This narrative was so entrenched in American culture that women who felt a lack of satisfaction with the homemaking status were embarrassed to even admit that they had a problem. It was literally ignored and largely went unattended for so long, it was eventually declared as ‘no problem’.

But although women were unaware of the problem they had and even uncomfortable admitting having it in the first place, they nevertheless felt that something was wrong with their lives, that they had a problem. For that reason, in the Feminine Mystique, Friedan defines it as a ‘problem with no name’. This unnamed problem was common and widespread across classes and ages, and women who experienced it exhibited symptoms of unexplained need to cry/grief, lack of desire and a deep sense of emptiness. Women who showed these symptoms were given tranquilizers and psychiatric treatment since it was regarded as a mental problem.

The falsehoods perpetrated by the feminine mystique about the happiness of the domesticated wife and her source of this happiness would be exposed in the early 1960s when the media started to report about the widespread phenomenon of miserable housewives in modern suburban America. Research by psychiatrists indicated that single women had happier and more fulfilled lives than married women, and the artificially cultivated ‘happy wives’ narrative was exposed, since the unhappiness of most wives became a mainstream discussion in America. The problem that had for long been kept in the shadows with no name, had eventually come out in the open, and there was no denying that it was indeed a problem and that it existed.

According to Friedan, the complications resulting from lack of happiness among American housewives was not because of marital or material problems, rather, it was a result of a series of unanswered desires and personal yearnings brought about by the contemporary American social setting at the time, which Friedan describes in the ‘feminine mystique’. Doctors suggested sexual dysfunction as the cause of this unhappiness; that because husbands were too busy with their work, they did not spare enough time to satisfy their wives’ increasingly growing sexual desires. The assumption in this diagnosis was that since women had the ‘easy/soft life’, all they would think of was sex and their desire for sexual gratification was increasing at a rate that ‘busy’ working men wouldn’t catch up with.

Psychiatrists also weighed in with suggestions that the housewife’s lack of satisfaction/happiness was because she had been locked away in the home, and her only sense of feeling alive was the presence of her husband, that she was forced to wait for when her husband’s busy schedule would allow for rare opportunities for her to feel alive. The second Kinsey report in 1953, which suggested that the unhappy American housewives were suffering from the same problems as those who were sexually oppressed, hugely undermined the perceptions of the ideal woman in conservative America. This unnamed problem was also spreading to the children of the unhappy wives, as the symptoms of low self-esteem, lack of self-confidence and boredom were increasingly being observed in children whose mothers’ dependency of their fathers was evident.

In describing the ‘feminine mystique’ and ‘the problem that has no name’, Friedan examines whether the ‘problem that has no name’ is in any way connected to the daily routine of women’s domestic work, and whether the repetitive and demanding nature of the domestic chores overwhelm women so much that they don’t have any free time for themselves, which caused them to become depressed. Depression, coupled with repetitive tiredness and diminished ability to focus on self, caused women to become sick, needing treatment. In seeking to diagnose this sickness, research by medical and psychiatric professionals postulated that being bored at home all day was the cause of women’s fatigue. However, Friedan argues to the contrary that in trying to remain compliant to the society’s expectations, women find themselves locked up in an invincible trap of misinterpreted ideas, unrealistic choices and half-truths.

The 1950s modern/suburban American women, though seemingly happy in their marriages, were feeling a sense of emptiness, unfulfilled, dissatisfied, without purpose and meaning in their lives. Since they were supposed to be kept in the home as a way of creating space for the men, socialization was tailored towards developing the idea that the women’s place is supposed to be in the home, and therefore by affording them the space to be in their ‘natural place’, women would be graceful to their male benefactors, and be happy and content. For many men (including ‘expert psychologists’), it made no sense that women could actually feel unhappy yet they were being afforded everything that any woman could ever want (freedom in the home to choose the furniture, the décor, the family car, social connections with fellow women in the neighborhood). It was unthinkable to the men of the time that women would want to go out and get involved in the daily struggles of life, succeed in them and even draw satisfaction while doing it.

That is why it was puzzling for the men that women could feel empty and be depressed when they were actually being given everything they are meant to have without even having to struggle for it. How could women find issue with a soft/easy life at home when it’s all just given to them on a silver platter! However, it must be pointed out that the patriarchal conservatives forgot, or merely wished to cover up the fact that women were not always stacked away in the kitchen. When there was need for them to come out of the kitchen and fill up the positions left behind by men, in order to keep the country going, women welcomed the task and excelled at it. So much so that the American economy actually thrived during the second world war (while men were away and women were in charge) and its immediate aftermath. Women had tasted the feeling and satisfaction of being more than just the wife at home and that could not be wiped out of their minds.

Friedan in her book, offers albeit silently, the assumption that the pre-second world war women might have not had such urges/desires because the home was all they had ever known throughout the years. They had no reason or even the basis to desire for anything outside the home. That was not the case with the 1950s women, because they themselves had been pulled out of the home out of necessity and had experienced life outside the home. Or at the very least, if they were teen mothers who were too young to partake in the out-of-the-home work changes of the mid-to-late 1940s, they had been told by their mothers who did. Therefore going forward, whether by experience or being told about it, women had learnt that they were not meant for ‘only’ the home as was being postulated by the conservative patriarchs of the time.

The hierarchy of needs theory of Abraham Marslow comes in here. By filling in for absentee husbands/fathers during the Second World War, women discovered their worth outside the home, and with it realization that being confined in the home was just a socialization construct and not their biological limitation. According to Marslow’s theory, individual behavior is dictated by five basic human needs (physiological, safety, love, belonging, esteem and self-actualization). To Friedan, the 1950s women were no longer content with physiological, safety and love needs since they had tasted esteem and self-actualization. And much as they were forced to give it up when men returned to reclaim their ‘space’, they could not completely abandon or forget the psychological satisfaction that came with esteem and self-actualization.

According to Friedan, the only way to get out of the trap of the problem without a name can be found by analyzing the problem through biology, sociology and psychology, which were always ignored in the then academic research on the problem. The various factors which resulted into women being locked away in homes and which led to their developing feminine depression, according to Friedan, included; the neighborhood communities/conformities, the re-emergence of early marriage preference and appeal/desire for large families, appeal for natural birth and breastfeeding and complete disregard for sexual satisfaction in discussions about women. This was compounded by the fact that much as it was widely acknowledged that women, and mostly married women at the time, had a problem (though an unknown problem, but a problem nevertheless), most of the so-called experts that researched and diagnosed this unknown problem were men, and the women who were experiencing the problem were sidestepped in the attempts to understand the problem.

To Friedan, there was a connection between the above depressing and physiological phenomena with the 1950s women who at the time experienced sexual dissatisfaction and frigid desire for it, menstrual complications, nervous breakdown, fear of pregnancy and postpartum depression. In other words, women were to be subjected to the burden of sex purely for purposes of reproduction without the benefits of sexual pleasure. This increased cases of adultery and/or suicide tendencies among mid-age married women. The conservative patriarchal America could not have its women, who were then effectively used as child factories and domestic labor providers, to be lost through suicide, yet even when faced with such dire results, male dominated America could not fathom having women’s voices heard.

In conclusion, Betty Friedan says that the problem that has no name (that is lack of satisfaction with their lives, and depression among most married women in the 1950s America) which was espoused in the feminine mystique, was not because they were not feminine, but rather because women had acquired education and become self-aware. Women knew that they had the capacity to do more, to achieve more, and so they desired for more than just being at home bearing children and raising them. The problem that has no name not only elaborates the struggles of the 1950s married American women, but also the resultant problems that affected their husbands and children. By this, Friedan was trying to push the narrative that the problem that has no name was not only a women’s problem but a problem for the whole society, and understanding its core cause would lead to a clear understanding of the social fabric and development of the American society as a whole.

References

Friedan, B. (2013). The Feminine Mystique. (50th Anniversary Edition). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Horowitz, D. (1996). Rethinking Betty Friedan and the Feminine Mystique: Labor Union Radicalism and Feminism in Cold War America. American Quarterly, 48(1) 1-42. Print.

Meyerowitz, J. (1993). Beyond the Feminine Mystique: A Reassessment of Postwar Mass Culture, 1946–1958. The Journal of American History, 79(4) 1455-82.

Napikoski, L. (2020, August 27). What Is the Problem That Has No Name? Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/problem-that-has-no-name-3528517

Turk, K. (2015). To Fulfill an Ambition of [Her] Own”: Work, Class, and Identity in the Feminine Mystique. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 36(2) 25-32.