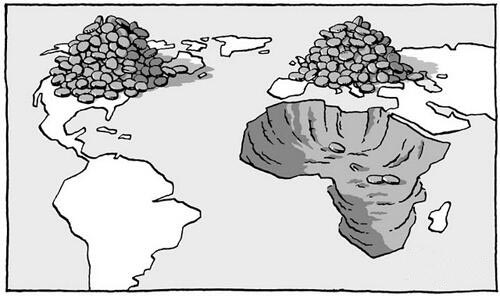

After almost 50 years since its publication, Walter Rodney’s book “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” still presents a fascinating read, given how little things have changed. If anything, it shows how resilient neo-colonialism has proved to be as well as how fundamentally untouched its economic setup remains. The apparent paradox whereby the richest continent on earth (in natural resources) is also the poorest hasn’t lost any of its bitter irony. Africa is at the very center of global economic interests, with major powers still scrambling over its highly lucrative resources. Though stereotypically perceived as the quintessential recipient of humanitarian aid, Africa still is, for the most part, being deprived of (its own) wealth rather than benefiting from charitable, outside help.

If one wants to trace the genesis of this historical theft, often associated with or mistaken for ‘civilization,’ Rodney’s book is as indispensable as it is exhaustive. From the outset, Rodney, a Guyanese historian, revolutionary, and academic disallows any moralistic understanding of colonialism, resolutely moving beyond accusation and guilt. While the dominant discourse around postcolonial reparations tends to be conducted in strict ethical terms, Rodney’s book compellingly links racial inequality with social injustice.

In his book, Rodney clearly indicates that it is the economics of colonialism he is after, not its morals or evident lack thereof. Even when tackling the ancillary apparatuses of colonial rule such as culture and education, the relation between white supremacy and the exploitation of resources is always brought to the fore. So much so that Rodney concludes that ‘African development is possible only on the basis of a radical break with the international capitalist system.’ The ultimate responsibility for the emancipatory struggle falls on the shoulders of Africans, he thought, implicitly warning that the benevolence or philanthropic charity of post-colonial powers will never be a solution.

The key question that Walter Rodney felt compelled to answer before venturing further in his militant diagnosis of Africa’s ills, was what constitutes development, and, conversely, what exactly do we mean by underdevelopment? He stresses how development should not be seen merely as an economic phenomenon but rather as an overall social process shaping and being shaped by the way societies came to be ideologically structured. Most crucially, Rodney note that ‘underdevelopment is not merely an absence of development’, if anything it’s a by-product of it, its indirect consequence. There cannot be development, that is, the accumulation of wealth and expertise derived from the exploitation of natural resources and human labor, without its flip side — underdevelopment.

The latter therefore denotes a relationship of exploitation, of one country by another in the colonial case, or one race over another in the apartheid case and any other case. The two phenomena are by no means natural or dependent on the superior ingenuity of one particular people or race. Rodney asserts that development and underdevelopment are politically determined, at the heart of their correlation we inevitably find exploitation. He points out that it would otherwise be difficult to explain why some of the poorest nations in terms of natural resources are among the richest on earth; their wealth was derived from the violent appropriation of other countries’ wealth.

The structural dependency that came to characterize the political and economic relation between Africa and Europe is to be traced back to a foundational moment for the modern history of the African continent: slavery. All the premises that still determine the current predicament of most African countries were laid out in the genocidal days of the slave trade. It was then that the cultural and social traditions of basically an entire continent were extirpated, its population subjected to a mass dislocation, the likes of which humanity had never seen before nor has it experienced since. Once again Rodney insists on linking the brutality of slavery to its financial rationale by quoting the English commercial expert Malachy Postlethwayt, who in 1745 enthused that, ‘British trade is a magnificent superstructure based on an African foundation.’

The comparative analysis of “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” does not exclusively focus on its titular assumption, but on its reverse deduction too. Slavery was in fact the engine of industrialization and as a matter of consequence the very basis of Western development and global supremacy. Without the stolen gold from Africa, Amsterdam would have never emerged as the financial capital of Europe at the time; and when in 1663 the English named their new coin ‘Guinea,’ it was not by coincidence but rather an acknowledgement of where the gold that made those coin was robbed from. The very poles of the Industrial Revolution, like Liverpool for instance, ‘depended first of all on the growth of its port through slave trading.’

Racism in Rodney’s analysis cannot be separated from the divisions created by the dominant economic system, which doesn’t mean that white supremacy did not evolve into its own cultural pathology. But to try to solve racism, according to Rodney, without looking at its economic purpose is delusional at best. ‘No people can enslave another for centuries without coming out with a notion of superiority,’ the author observes, ‘white racism was an integral part of the capitalist mode of production.’ This is a distinctive clarification that the book argues throughout, pointing out that ‘it is mistakenly held that Europeans enslaved Africans for racist reasons. European planters and miners enslaved Africans for economic reasons.’

In conclusion, Walter Rodney in his book “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” notes that while it’s impossible to calculate the impact of the slave trade and colonialism, it is clear how it has virtually deprived Africa of any developmental opportunity, condemning it to a subsidiary role. The continent and its resources had to be sacrificed on the altar of European expansionism and its priced economic growth. Material disparity obviously led to political, cultural, and, most crucially, educational inequality. Europe cultivated its freedoms, human rights, and cultures, while its colonies were saddled with violence, exploitation, and misery.

References

- Woodis, J. (1960). Africa, the Roots of Revolt. London: Lawrence and Wishant.

- Campbell, H. (2005). “Walter Rodney, the Prophet of Self Emancipation,” Pambazuka News, May 12, 2005, https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/walter-rodney-prophet-self-emancipation.

- Clairmont Chung, C. (ed) (2012). Walter Rodney: A Promise of Revolution. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Drayton, R. (2022). The Caribbean Origins of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. African Economic History 50(2), 17-21.

- Fletcher, B. (2022). Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa: The Continued Relevance of a Landmark Book, Cuny School of Labour and Urban Relations.

- Green, R.H. (1975). “Review of ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’, by W. Rodney”. Review of African Political Economy, 2, 117–120.

- Harman, C. (2008). A People’s History of the World: From the Stone Age to the New Millennium. London: Bookmarks,

- Rodney, W. (1982). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press, Washington D.C